This photo showing William H. Howard at approximately 14 years of age (on left) is the only known photo of William H. Howard, firstborn child of W.D.M. and Agnes Poett Howard. Image courtesy: Howard Family Collection

William Henry Howard (1850-1901) was 29 when his mother Agnes married for a third time in 1879. Her new husband Henry P. Bowie was 31 years old. Agnes was 46.

At the time of his mother’s new marriage, William had been married for seven years. He and his wife Anna Dwight Whiting, from a prominent Boston family, had been living in Paris. Their son Edward W. Howard was born in Paris in 1878.

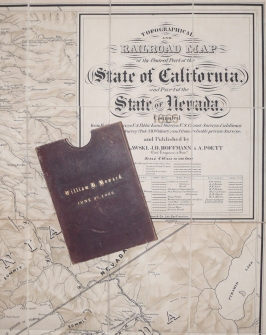

At the age of 16, William H. Howard received a leather-encased railroad map co-published by his uncle Alfred Poett, an engineer for the Central Pacific Railroad. Image courtesy: Howard Family Collection

Both William and Anna were raised with a sense of their families’ importance in the development of America. Anna’s family roots in Massachusetts predated the American Revolution.1 William was the firstborn child of the first President of the Society of California Pioneers. Near his sixteenth birthday, young William was given a leather-encased topographical and railroad map of central California with his name embossed in gold. William’s uncle, Alfred Poett, an engineer for the Central Pacific Railroad project—the monumental project that opened up the West for development by linking America’s coasts by rail in 1869—co-published the map. The gift carried an implicit message to the youth as he was about to enter adulthood: You are from a line of men who have achieved great things for this country; go and do likewise.

The William H. Howards commissioned monogrammed china while living in Paris. Image courtesy: Howard Family Collection

William and Anna lived an opulent life. While in Paris, they had china commissioned for them with their entwined initials. In San Mateo, they commissioned a huge brownstone home, designed by New York architect Bruce Price (Emily Post’s father), to be built near the property that William inherited from his father, W.D.M. The home, which the Howards called Uplands, was designed to impress. It included elaborate woodwork and stone masonry.2

After William’s mother Agnes married Henry Bowie in 1879, the Bowies went abroad with Agnes’s four younger children in tow. The one-year honeymoon turned into two and the Bowies remained in Europe. During this time, William helped manage El Cerrito for his mother and her new husband.

The Howards’ home, Uplands, was designed to impress visitors. In 1889, cattle and castles (like Uplands) coexisted on the Howards’ Rancho San Mateo.

Image courtesy: Howard Family Collection

In addition to San Francisco real estate, the family business interests included a farming, dairy, and cattle business in San Mateo. William worked with his mother’s chief gardener, John McLaren, to continue to improve the Howard property. At that time, Coyote Point was almost an island, surrounded on the south and west by marshland. Howard worked to fill in the marsh to make the land more saleable in the future. McLaren, supervising large crews of Irish and Chinese workers, planted 70,000 trees on Coyote Point.

William Howard was a prominent member of the growing community of affluent landowners on the mid-Peninsula. In the early 1890s, another second-generation wealthy peer, Francis Newlands, suggested that the mid-Peninsula needed a country club to cater to local residents’ needs and to promote real estate sales. Howard agreed. William H. Howard was one of the founding members of the Burlingame Country Club, formed in 1893. When the club decided that they needed a stylish train station where they could greet their incoming San Francisco guests, Howard stepped forward and donated the land. The club chose Howard’s younger half-brother, George, then 30 years of age, to be the architect. The station, completed in 1894, is the design of George H. Howard and his partner Joachim Mathiesen.3 Unfortunately, the Howards’ mother Agnes was never able to see the train station her son designed. She died in 1893 at the age of 60.

The unmarked mausoleum of William H. Howard’s mother, Agnes Poett Howard Howard Bowie, sits high above the bay in St. John’s Cemetery, San Mateo, California. Image courtesy: Silicon Valley Historical Association/Sally McBurney

Because Agnes’s third husband Henry P. Bowie was Catholic, St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church did not allow her to be interred in the church next to her first and second husbands, W.D.M. and George Howard. Her widower Henry Bowie and her children instead arranged to have a large mausoleum built for her at St. John’s Cemetery. The classical columns and style of the mausoleum suggest that her son George, the budding architect who was deeply influenced by the Grand Tour of Europe that the family took when he was 15, may have had a role in the design of her tomb. Her husband Henry was 45 at her death. Her son William was 43 and son George was 29.

Perhaps to meet the expenses of his opulent lifestyle, William began to sell some of his property in the 1890s. As early as 1889, he began subdividing his inherited portion of Rancho San Mateo. The first subdivision was on a narrow sliver of land in San Mateo just east of the railroad tracks and north of downtown.4 Later, that subdivision would be expanded both to the east and west.5 In 1894, Howard sold his beloved home Uplands to another second-generation Peninsula man, Charles Frederick Crocker, the namesake and oldest son of one of the “Big Four” California railroad men.6 Then in 1896, Howard created Burlingame’s first subdivision, which extended from Burlingame Avenue on the north to Peninsular (as it was then known) in the south and from El Camino Real to Dwight Road.

By the time Howard subdivided his property in 1896 in what is now Burlingame it was clear that he was overextended and experiencing cash flow problems. His Burlingame lots did not sell fast enough to prevent a foreclosure action on San Francisco property. On August 27, 1896, a San Francisco Call headline blared “The Hibernia Savings and Loan Society Sues W.H. Howard: Over $150,000 involved.” Howard’s financial troubles must have been a source of embarrassment for him: The Hibernia bank was owned and operated by the Tobins, fellow Burlingame Country Club members and mid-Peninsula country homeowners. As if to indicate that the legal action was not taken lightly or prematurely, the article went on to say that Howard had been in default on the loan for more than seventeen months. The financial problems must have added to fissures in Howard’s marriage. By 1900, Howard’s wife, Anna Dwight Whiting Howard, had moved back to Boston and was living at 209 Beacon Street with two of their children, Frances Sargent Howard and John Kenneth Howard (both unmarried at the time) and her mother, Rebecca Bullard Whiting.

On October 20, 1901, the San Francisco Call reported that William H. Howard had died that morning, after a long illness with Bright’s disease.7 He was 51. Less than a week after Howard’s death, his will was filed for probate. The San Francisco Call reported that the bulk of the estate was left to Howard’s four surviving children, with his widow getting only one-fifth. The headline was: “Widow is dissatisfied with the bequest in her favor and may contest.” Eventually a compromise was reached. Anna agreed to split the estate equally with her children, although there were later lawsuits over the details of the split. The estate was rumored to be substantial—as much as $500,000.

Meanwhile, William’s closest half-sibling, George H. Howard, was also making headlines.

Continue reading the Founding Families story –>