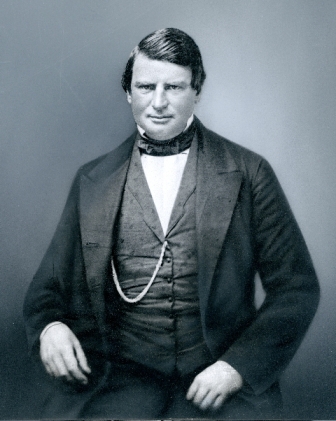

In June of 1849, William Davis Merry (“W.D.M.”) Howard, a tall, handsome, dynamic man, stood on the San Francisco bay front eagerly awaiting a ship from Valparaiso, Chile. A merchant mariner, 30-year-old W.D.M. had been trading cowhides and other goods between the California coast, then a province of Mexico, and his hometown of Boston for over a decade. Suspecting that California would become an important trading center as the United States continued to expand westward, W.D.M. invested much of his profit in real estate. By the summer of 1849, at the start of California’s Gold Rush, he was already a well-to-do man.

W.D.M. liked to meet the incoming ships, ever alert for new business opportunities. However, when he first saw 16-year-old Agnes Poett step off the ship from Valparaiso, Chile, he saw opportunity of another sort. Within one month, W.D.M. and Agnes married and within one year Agnes gave birth to their first son.

At least that is the story that has been handed down through the Howard and Poett families for generations.1 Others believe that the marriage was an arranged one, uniting the eligible 16-year-old Chilean beauty with the 30-year-old lonely, but energetic and successful, widower in a city where women—at least the ones whom respectable men would consider bringing home to mother—were scarce. Regardless of why they married, once they did join in holy matrimony, the new couple contributed extensively to virtually every one of San Francisco’s nascent civic institutions, including the beginnings of police and fire departments, schools, hospitals and a church—enough so that a major San Francisco street south of Market was named after them.

Already present and trading in San Francisco in 1847, W.D.M. was one of the first to learn of the discovery of gold. On June 11, 1848, he wrote to his trading partner in Boston and requested that he fill a ship bound for San Francisco immediately. With great excitement, W.D.M. described: “[I]t is about six weeks since the discovery . . . People here are perfectly crazy. This town has been almost deserted . . . they have paid as high as $30 for a ¼ of beef rather than go 20 miles to obtain it for $3 & $4 . . . Crews are leaving their vessels . . . we shall be famished this year if produce is not brought from foreign ports . . . I recommend your fitting out an expedition immediately . . .”2

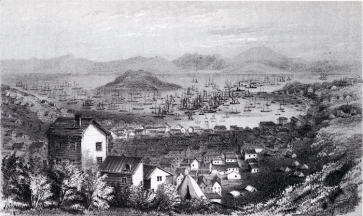

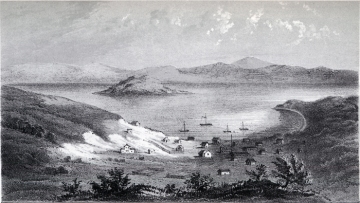

Pre-Gold Rush San Francisco, 1848

Image courtesy: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Entrepreneurs like W.D.M. who were already resident in San Francisco before the Gold Rush had inside knowledge that instantly elevated their status in the community and made them well-positioned to benefit from the influx of fortune seekers. Before gold was discovered in 1848, San Francisco’s population was estimated to be a mere 800 people; by the following year the population had swelled to over 25,000.3 W.D.M. knew where to get provisions of all sorts, knew the best travel routes, knew where to find accommodations.

An extremely energetic and industrious man, one can imagine W.D.M. directing traffic at the waterfront while barking buy and sell orders from his big barrel chest. When the U.S. Senator’s daughter and socialite Jesse Benton Frémont arrived by ship in June of 1849, several weeks ahead of her explorer husband, it was W.D.M. who sent his private launch to her ship to greet her and welcome her to San Francisco.4 When half the population was estimated to be living in tents in June of 1849, W.D.M. knew how and where to order prefabricated houses to be sent to San Francisco “ASAP” to meet the growing need. By 1850, one gets the sense that W.D.M. and other early residents of San Francisco wanted a “badge” by which to identify themselves to newcomers: In that year they formed the Society of California Pioneers, a club that requires, as a condition of membership, that members prove they (or their ancestors) were living in California prior to January 1, 1850. W.D.M. served as the Society’s first president.5

The one thing this vigorous man did not have in the summer of 1849, while he paced the waterfront waiting for the ship from Valparaiso, was a wife. His first wife, Mary Warren, had died in childbirth in Honolulu during the winter of 1848. Women suitable as wives were rare in Gold Rush California. When W.D.M. married his second wife Agnes, he was protective and solicitous of her. Not long after young Agnes disembarked from her ship in June of 1849, W.D.M. bought her a home in San Francisco, perhaps in an effort to assuage any doubts she may have harbored about the desirability of her new city, where most people were living in tents or abandoned ships. The home was undoubtedly purchased at great expense, since Jessie Benton Frémont, who arrived in San Francisco the same month that Agnes did, reported that in June of 1849 there were only “three or four regularly built houses in San Francisco . . . the rest were canvas and blanket tents.”

One year later, in 1850, the same year that their first son William H. Howard was born, W.D.M. and Agnes added to their real estate holdings: They became the sole owners of 6,500-acre Rancho San Mateo, some 20 miles south of San Francisco.6 The Howards probably did not spend a lot of time at the San Mateo ranch at first. After all, W.D.M’s businesses and civic responsibilities were in San Francisco. As early as 1847, W.D.M. had assumed a leadership role in the small hamlet, serving on an early town council. After the Gold Rush, he continued to serve the public, first on a force of “special constables” to combat The Hounds7 and later as a Vigilante.8 He was also a commander in the California Guards.9 After statehood, there were also legal matters that needed attention. W.D.M. served as a supernumerary delegate to the state constitutional convention. He was called as a witness to testify in numerous court cases brought to clear title to the old Spanish land grants. He also served as the executor of the estate of another well-known merchant, William Leidesdorff. A San Francisco fire in the early 1850s nearly wiped out W.D.M.’s numerous residential and business properties and this crisis demanded his attention.10

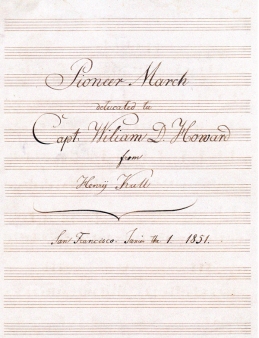

The cover page of the sheet music for the “Pioneer March” by Henry Kull.

Image courtesy: Howard Family Collection

Listen to the Pioneer March.

Lastly, W.D.M.’s social life, and to the extent Agnes had one in the rough and tumble Gold Rush days, then hers as well, were in San Francisco. A grand ball thrown by the Society of California Pioneers to celebrate California’s admission to the United States was so grand it was said to have “put most of the members in bed for a week and bankrupted the society’s treasury.”11 The Society also elected a board that met in San Francisco to conduct its business. In honor of its first President, Henry Kull, a well-known musician at that time, wrote a “Pioneer March” and dedicated the piece to Captain W.D.M. Howard.

By late 1852, the formerly robust W.D.M. began to suffer from poor health. The family, which by that time had grown to include two young boys, took an extended trip in 1853 and 1854 to his family’s home in the Boston area to nurse his health. Not long after they returned to the Bay Area, he died, on January 19, 1856. The Daily Alta California reported the following morning that “Capt. W.D.M. Howard died at his residence in the city this morning at 9 o’clock. He was one of the Pioneers of California and has been one of the most successful businessmen of San Francisco, having amassed a princely fortune since his residence in this State.” W.D.M. was 36. Agnes, his widow, was 23. His young son William H. Howard was 6.

Continue reading the Founding Families story –>